The United Nations states that, “Bullying affects a high percentage of children, compromising their health, emotional well-being and academic work, and is associated with long-lasting consequences continuing on into adulthood.”[1]And bullying could get worse as children return to school after three school years of a lot of isolation. Teachers say serious behavior issues like emotional dysregulation and disruption are more common than they used to be pre-pandemic[2]. With bullying so prevalent and aggressive behaviour increasing, Roots of Empathy “Tiny Teacher” school programs are needed now more than ever to guide children in the direction of helping more and hurting less.

As Mary Gordon, Founder and President of Roots of Empathy said in a BBC interview, “We use a baby as a vehicle to find the baby’s vulnerability and humanity – so they can flip if back to their own experiences… It’s very hard to hate someone if you realize they feel like you. It is very hard to be bullying someone if you realize that.”

What is bullying?

There are dozens of definitions of bullying. We prefer to look at bullying as hurting someone’s feelings intentionally by calling them names, making fun of them, or actually physically hurting them. What is universal about the impact of bullying, is that people feel “gutted”, shocked, hurt and helpless. Social exclusion is a type of bullying that is not often talked about. That’s repeatedly and purposely leaving someone out. It’s not bullying if there is no intent, but when you’re left out, it certainly isn’t easy to make that distinction.

And there is too much bullying

Canada, the United States (US), and the United Kingdom(UK) are no exceptions. According to Public Safety Canada[3], 47% of Canadian parents have at least one child that has been a victim of bullying and one-third of the population experienced bullying as a child. In the US, 22 % of students 12 to 18 reported being bullied in 2019, and it is higher – 27 to 28 % – for 6th, 7th , and 8th graders. [16] As for the UK, one indicator from a OECD 2018 survey showed that 29% of English secondary school heads had reports of bullying amongst students. [17] In schools, it occurs in classrooms (29.3%), hallway or lockers (29%), lunchroom/cafeteria (23.4%), gymnasium (19.5%), bathroom (12.2%) and recess playground (6.2%).[4] .

Being bullied is a serious risk factor for mental health and academic achievement

Anxiety, depression, and self-harm behaviours including contemplation of suicide are some of the reported effects of bullying.[5] And, further research indicates that children who have been bullied are at higher risk for mental health problems as an adult.[6] Being a target of bullying in childhood not only jeopardizes young victims’ mental health and well-being at the time and late in life, it also impacts academic achievement.

Being bullied makes children want to miss school and not want to engage

With confidence completely shaken, victims of bullying are at a higher likelihood of being absent from school[7] and of dropping out.[8] Also, there is growing evidence that students who are bullied, don’t engage as much in their class for fear of being further targeted (raising hands, group discussions). This can result in being characterized as a low achiever.[9] That can bring on more bullying by peers, less understanding around potential by educators, and consequently perpetuate more loss of confidence. According to a 13-year study from K to Gr 12 from the American Psychological Association, “As a potential determinant, it is conceivable that peer victimization’s toll on children’s achievement stems from its capacity to undermine children’s school engagement.” (Ladd et.al)[10]. It would seem that the more that a student is bullied, the more their academic achievement is impacted.

How does the Roots of Empathy Classroom Program significantly reduce bullying?

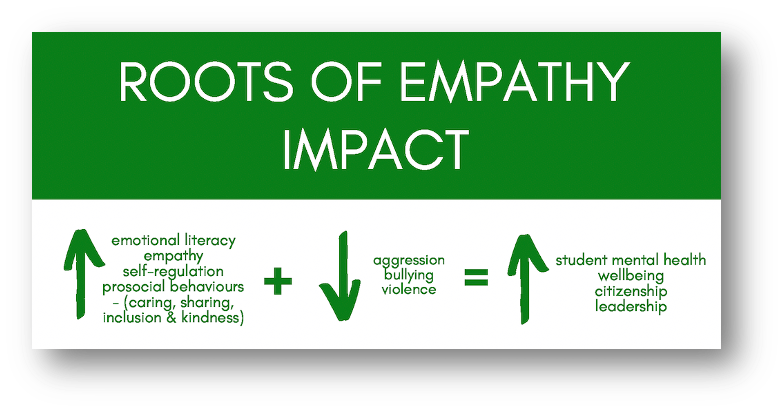

The “emotional literacy” taught in the program lays the foundation for children to understand their own feelings and the feelings of others. And there is independent evidence that this works to help reduce aggressive behaviour and bullying significantly.

What about the bully – we need to be worried about them too.

Aggressive children often have fewer cognitive, social, and emotional skills available to them and they are more likely to be rejected by other children and are less likely to get along with teachers (Schick et al., 2016; Lynn Mulvey et al., 2017; Decker et al., 2007; McGrath et al., 2015)[11]. Children who display early aggressive behaviour are at high risk for many negative outcomes, including depression, suicide attempts, alcohol and drug abuse, violent crimes, and neglectful and abusive parenting. (Tremblay et al., 2004)[12]

Teacher Testimonial for Roots of Empathy (ROE)

”At the beginning of the year there were some students who came to my class with some bullying behaviors that included verbal, physical and social issues. I was actually wondering if ROE would be a good fit as I was worried those students would be too disruptive, say things that were not appropriate and exhibit unacceptable behaviours when our group instructor came. As the day drew closer to when Baby Chelsea would come, I was happy to see the progress those students had made from the beginning sessions to this day! Through the quality children’s literature that was read to the students along with the class discussions on many issues, I had begun to see a change in some inappropriate behaviors and now saw students showing more caring, friendly attitudes and an overall concern for their friends in their class and especially towards "Baby Chelsea"! One of those students I was concerned about even asked if he could wear his tie to school the day Baby Chelsea came to look his best! Sure enough, he came to school wearing his bow tie! His mom said he was adamant that he wanted to wear it because it was going to be a very special day!

Host Teacher TestimonialNewfoundland and Labrador Wings Point Riverwood Academy, 2019

More teacher and educator testimonials here

Evidence-Based Result: Bullying behaviour is reduced in classrooms that have had the Roots of Empathy program.

- “Analyses revealed that, whereas children in the ROE program group evidenced significant decreases in their relational aggression from pretest to post test… control children evidenced significant increases in their proactive and relational aggression…” (Schonert-Reichl et al., 2012, p. 12). [13]

- In a cluster, non-randomized, matched-control trial, those who received the ROE program had a significant decrease in aggression compared with those who did not receive the program. These results were maintained one year after program completion (Latsch, et al., 2017).[14]

- In a cluster, randomized control study in Manitoba, there was a significant decrease in teacher-rated psychical aggression as well as indirect aggression compared with those who did not receive the program. These results were maintained up to three years after program completion (Santos et al., 2011). [15]

Over 2 decades of independent research has shown that children in the Roots of Empathy program experience lasting increases in prosocial behaviours, an increase in empathy, and a decrease in aggressive behaviours and bullying. Our program has been cited in more than 1000 academic papers. For more information on the research, please got to: https://rootsofempathy.org/research/

Student Testimonial About Roots of Empathy (1.30 min video)

See how Roots of Empathy works – and how it works to reduce bullying

Roots of Empathy, our flagship program created by Mary Gordon in 1996, is centred around the novel concept of having a baby become the “teacher” in a classroom. Parents volunteer to bring their babies, starting from 2-4 months old, into a classroom every month. During these visits, a ROE Instructor (a trained volunteer) will guide a discussion with the children around a green blanket, encouraging them to read the baby’s emotional cues and take the baby’s perspective.

Through this experiential learning, the children develop an understanding and vocabulary for the baby’s feelings. The ROE Instructor may ask: How do you think Baby Zoe is feeling today? A child may respond: she seems sad. Her mom said that when they came through the front door of the school the recess bell rang and it frightened her. Why do you think Baby Mohammed is clinging to his mom? Maybe because she’s not used to us and feels shy.

This kind of observation and thoughtful reflection allows children to gain insight into how others may feel – even if others don’t verbalize their feelings. The process also gives children the tools to help understand, identify, and talk about their own feelings, even the deepest and most troubling – helping them become emotionally literate and develop empathy. Participating children will experience 27 classes specialized curriculum according to their age level; Kindergarten (ages 4-5), Primary (ages 6-8), Junior (ages 9-11), and Senior (ages 12-13). It is delivered on three continents, and in multiple languages.

To go back to reducing bullying, through the process if the program, children realize – they would never bully this little baby – they realize how bullying makes others feel. In short, Roots of Empathy helps children understand our common vulnerability – we are the bigger babies around the green blanket.

A culture of caring is important in a classroom to help everyone feel that they belong

Children who receive the Roots of Empathy school program are not only less likely to physically, psychologically and emotionally hurt each other but also more likely to challenge cruelties and injustices. Messages of social inclusion and activities that are consensus building contribute to a culture of caring which changes the tone of the classroom.

“We focus on setting a place at the table for everybody, whether a high chair, wheelchair, or a rocking chair. Inclusion means identifying our differences and celebrating our sameness; it allows us to build on our shared humanity.” – Mary Gordon

Help Us Reach Our Goal

We can’t thank you enough for your ongoing support, volunteerism, and donations that make all the difference in children’s empathic development and well-being.

We’re excited about returning to classrooms in person delivering the Roots of Empathy programs to children. By donating to us, you help us reach even more children. Please consider a donation today.

See the BBC interview: https://rootsofempathy.org/the-baby-tackling-bullying-at-school/

See the CNN interview: https://rootsofempathy.org/babies-fighting-bullying/

References

[1] https://violenceagainstchildren.un.org/content/bullying-and-cyberbullying-0

[2] Multiple references: (a)Cohen & Willemsen, 2022; (b)Bayrami, 2022; (c) Alphonso, 2022; (d) GOV UK, 2022.

(a)Cohen & Willemsen. (January 2022). ‘Teaching has always been hard, but it’s never been like this’. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/teaching-has-always-been-hard-but-its-never-been-like-this-elementary-school-teachers-talk-about-managing-their-classrooms-during-a-pandemic-175006 (b) Bayrami, L. (May 2022). Key Findings: The Implications of Virtual Teaching and Learning in Ontario’s Publicly Funded Schools, K-12. Ontario Teachers’ Federation. http://www.otffeo.on.ca/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2022/05/Key-Findings-Lisa-Bayrami-The-Implications-of-Virtual-Teaching-and-Learning-in-Ontario’s-Publicly-Funded-Schools-K-12.pdf . (c) Alphonso, C. (July 2022). Summer school helping children close the pandemic learning gaps. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-summer-school-helping-children-close-pandemic-learning-gaps/ (d)GOV UK. (April 2022). Education recovery in schools: spring 2022. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/education-recovery-in-schools-spring-2022/education-recovery-in-schools-spring-2022

[3] Bradshaw, C.P. (2007). Bullying and peer victimization at school: Perceptual differences between students and school staff. 36(3), 361-382.

[4] As referenced in Lereya T, Copeland W., et. Al. Adult mental health consequences of peer bullying and maltreatment in childhood: two cohorts in two countries. The Lancet. Psychiatry. Vol 2 June 2015; p 524 (anxiety a, b) a. Stapinski LA, Bowes L, Wolke D, et al. Peer victimization during adolescence and risk for anxiety disorders in adulthood:a prospective cohort study. Depress Anxiety 2014; 31: 574–82. b. Sourander A, Jensen P, Rönning JA, et al. What is the early adulthood outcome of boys who bully or are bullied in childhood? the Finnish “from a boy to a man” study. Pediatrics 2007;120: 397–404., (physical) – Gini G, Pozzoli T. Association between bullying and psychosomatic problems: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2009; 123: 1059–65, (depression) Zwierzynska K, Wolke D, Lereya T. Peer victimization in childhood and internalizing problems in adolescence: a prospective longitudinal study. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2013; 41: 309–23. (suicide c, d) c. Winsper C, Lereya T, Zanarini M, Wolke D. Involvement in bullying and suicide-related behavior at 11 years: a prospective birth cohort study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2012; 51: 271–82.d) Brunstein-Klomek A, Sourander A, Niemelä S, et al. Childhoodbullying behaviors as a risk for suicide attempts and completed

suicides: A population-based birth cohort study.

[5] Lereya T, Copeland W., et. Al. Adult mental health consequences of peer bullying and

maltreatment in childhood: two cohorts in two countries. The Lancet. Psychiatry. Vol 2 June 2015; p.529

[6] Bullying and Absenteeism. Information for State and Local education Agencies. Department of Health and human Services USA, CDC. Retrieved Aug 18 at https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/health_and_academics/pdf/fs_bullying_absenteeism.pdf

[7] Preventing Bullying. Department of Health and human Services USA, CDC. Retrieved Aug 18 at https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/yv/bullying-factsheet508.pdf

[8] Wolpert, Stuart. Victims of bullying suffer academically as well, UCLA psychologists report. August 19, 2010. Retrieved Aug 19,2002 at https://newsroom.ucla.edu/releases/victims-of-bullying-suffer-academically-168220

[9] Ladd G,. Idean E. et al. Peer Victimization Trajectories From Kindergarten Through High School: Differential Pathways for Children’s School Engagement and Achievement? Journal of Educational Psychology 2017, Vol. 109, No. 6, 826–841 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/edu0000177 © 2017 American Psychological Association. P age 839

[10] Schick, A., & Cierpka, M. (2016). Risk factors and prevention of aggressive behavior in children and adolescents. Journal for Educational Research Online 8(1), 90-109. doi: 10.25656/01:12034. Decker, D. M., Dona, D. P., & Christenson, S. L. (2007). Behaviorally at-risk African American students: the importance of student–teacher relationships for student outcomes. Journal of School Psychology, 45, 83–109. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2006.09.004.

[11] McGrath, K., & Van Bergen, P. (2015) Who, when, why and to what end? Students at risk of negative student-teacher relationships and their outcomes. Educational Research Review, 14, 1-17.https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EDUREV.2014.12.001

[12] Tremblay, R. E., Nagin, D. S., Séguin, J. R., Zoccolillo, M., Zelazo, P. D., Boivin, M., Pérusse, D., & Japel, C. (2004). Physical aggression during early childhood: trajectories and predictors. Pediatrics, 114(1), e43–e50. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.114.1.e43.

[13] Santos, R.G., Chartier, M.J., Whalen, J.C., Chateau, D., & Boyd, L. (2011). Effectiveness of school-based violence prevention for children and youth: Cluster randomized controlled field trial of the Roots of Empathy program with replication and three-year follow-up. Healthcare Quarterly, 14, 80-90.

[14] Latsch, D., Stauffer, M., & Bollinger, M. (2017). Evaluation of the Roots of Empathy program in Switzerland, years 2015 to 2017. Full Report. Bern: Bern University of Applied Science.

[15] Santos, R.G., Chartier, M.J., Whalen, J.C., Chateau, D., & Boyd, L. (2011). Effectiveness of school-based violence prevention for children and youth: Cluster randomized controlled field trial of the Roots of Empathy program with replication and three-year follow-up. Healthcare Quarterly, 14, 80-90.

[16] National (16) National Center for education Statistics. Retrieved September 29, 2022 at https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=719

[17] https://www.oecd.org/education/talis/talis2018tables.htm, Chapter 3 What do teachers and schools do that matters most for students’ social and emotional development? https://doi.org/10.1787/888934224258, (EDU-2019-3480-EN) Table 1.3.45